Alain Ambrosi (Canada) is a designer and producer of intercultural projects, independent researcher, author, videographer and producer of the Remix The Commons Project.

Patterns of

COMMONING

Bisse de Savièse: A Journey Through Time to the Irrigation System in Valais, Switzerland

By Eric Nanchen and Muriel Borgeat

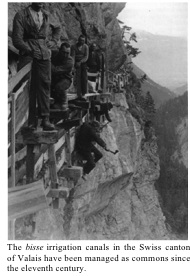

In Valais, Switzerland, a network of “artificial canals” was rediscovered in the 1980s. They were “drilled and built into mountainsides, enabling the irrigation so important to land cultivation by transporting water across several kilometers,” as Auguste Vautier recounts (1942:19). Above and beyond their original purpose, the canals have become important for tourism today, contributing to the establishment of popular hiking trails, among other things. The irrigation canals are of interest in connection with the commons because of their long history of collective management.

Irrigation canals were mentioned in the Swiss Alpine canton Valais for the first time in thirteenth century documents that referred to structures that had likely been built 200 years before. Yet it was not until the fifteenth century that the Golden Age of the bisses dawned. Historically speaking, the development of the network of canals can be explained by events that left deep scars across Europe: the plague of 1349 and the epidemics that followed. The population of Valais was hit hard by these epidemics and was decimated by at least 30 to 50 percent. The decline of population density in the Alps in turn meant that land that had previously been used for growing grain was freed up for other purposes. At the same time, the demand for beef increased sharply in the cities of northern Italy. These two factors prompted the farmers of Valais to increase their herds of cattle and to convert their land into hayfields. They had to build the famed canals to transport water from the mountains to their pastureland. So the owners of the hayfields and pastures joined forces, and “collective operations [began] which often involved the entire village community,” as one researcher of the canals, Muriel Borgeat, has said.

In the nineteenth century, population pressure and the expansion of vineyards sparked a new phase of irrigation canal construction. In 1924, there were 300 irrigation canals totaling approximately 2,000 kilometers (Schnyder 1924:218). The last survey in the canton of Valais, in 1992 (unpublished), found 190 extant irrigation canals spanning a distance of at least 731 kilometers.

One of these canals is part of the Savièse irrigation system. It was built in several stages. More than a century after it was put into operation in 1430, it was expanded through an impressive wall of rock in order to increase its holding capacity. Hundreds of years later, in 1935, a tunnel through the Prabé Mountain was finally completed, making it easier to maintain the system and to pipe the water across the high plateau. The sections of the bisse built at dizzying heights were then abandoned. Only in 2005 did some enthusiasts of the Association for the Protection of Torrent-Neuf1decide to reconstruct this emblematic part of the bisse with the support of the municipality of Savièse. This section bears witness to the high-wire acts undertaken by earlier generations in order to secure irrigation.

The traditional form of common management of the bisse has endured. Since the Middle Ages the feudal lords granted the rural communities water-use rights, either to the entire community or to a group of people who joined together in a community of users, a consortage. Such a consortage has always had a special statute that determines the rules for use of the system, details of construction (what, by whom, how), maintenance, financial management, and monitoring of the canal system. In the spring, the canals had to be cleaned, and sections damaged in the winter had to be repaired so they would again hold water. Women attended to sealing the wooden channels, collecting twigs and branches and stuffing holes. Today, municipal employees take care of this job, occasionally supported by passionate volunteers.

Members of the consortage were granted certain rights to use water proportional to the area of land they cultivated, and for a precisely defined period of time. Each family’s coat of arms and its allotment of water rights were carved into a wooden stick. The rights were distributed at regular intervals. “Water thieves” – people who violated the rules of distribution or disregarded the relevant time periods – were punished. “Water theft was considered a serious offense, and the community treated the thief with contempt” (Annales Valsannes 1995:348).

Managing the gates controlling the flow of water was a responsibility of great power because water supply was so fundamental to the farmers. Setting the gates was usually a task reserved for the canal guards (gardes des bisses) who saw to the proper condition of the system and guaranteed passage of the largest amount of water possible. Of course, this form of communal organization also reflected a commitment to shared values such as solidarity. Yet as historian and archivist Denis Reynard told us in an interview in July 2014, “It was first and foremost economic reasons that forced the landowners to join forces.

It was a way to keep the system going. It was always a necessity, first for farming cattle, and in the nineteenth century, for growing wine. Joint management was a good solution.” When we ask whether this management system will endure over the long term, he gets more concrete: “It works if people have a common economic interest – for example, in farming, cattle raising or growing wine. If that isn’t the case, then it has no future.”

The bisse irrigation canals in the Swiss canton of Valais have been managed as commons since the eleventh century.

Up to this day, the consortage of Savièse is responsible for irrigating the vines. Since common economic interests no longer connect the farmers as strongly as in the past, maintenance of the canals has become problematic. One possibility would be for the municipality to take over management of the system. The establishment of the Association for the Protection of Torrent-Neuf sparked new interest in the bisse as a piece of cultural heritage. “That made restoration possible, but it isn’t a consortage,” explained Reynard.

The Bisse de Savièse is majestic. It has been repaired, and it is located in the midst of a protected Alpine landscape. Thanks to the association, management today still functions similarly to the original system. Yet use of the system has changed. As a tourist attraction, cultural heritage and irrigation infrastructure – all at the same time – thebisse tells the story of the development of a Valais commons over the course of centuries.

References

Akten der Internationalen Kolloquien zu den Bewässerungskanälen, Sion, September 15-18, 1994, sowie 2. bis September 5, 2010, Annales valaisannes, 1995 and 2010-2011.

Reynard, Emmanuel. 2002. Histoires d’eau: bisses et irrigation en Valais au XVe siècle, Lausanner Hefte zur Geschichte des Mittelalters (Cahiers lausannois d’histoire médiévale) 30, Lausanne.ders. 2008. Les bisses du Valais, un exemple de gestion durable de l’eau?, Lémaniques, 69, Genf, S. 1-6.

Schnyder, Theo. 1924. “Das Wallis und seine Bewässerungsanlagen,” in Schweizer Landwirtschaftliche Monatshefte, S. 214-218.

Vautier, Auguste. 1942. Au pays des bisses, 2. Auflage, Lausanne.

Eric Nanchen (Switzerland) is a geographer and director of the Foundation for the Sustainable Development of Mountain Regions (www.fddm.ch). He focuses on development policy, in particular the effects of global and climatic changes on the Alpine world.

Muriel Borgeat (Switzerland) is an historian and project director at the Foundation for the Sustainable Development of Mountain Regions. Her research concerns the history of Valais and Rhône.